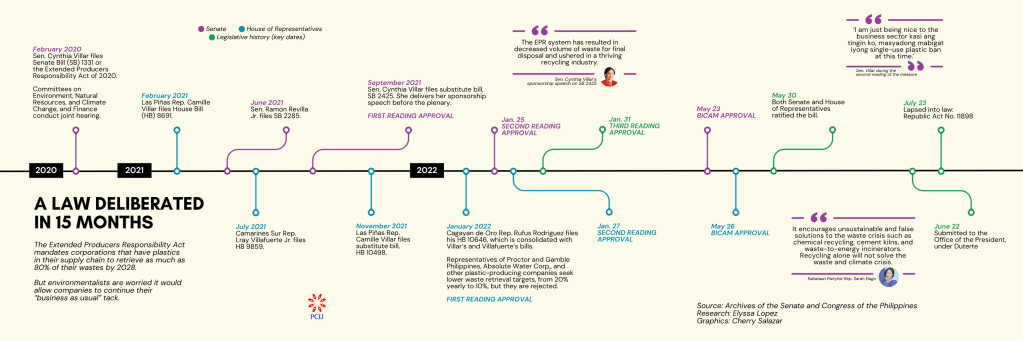

The law that could change the way plastics are sold and disposed of in the Philippines — a country long known to have relied on plastic sachets for both convenience and necessity — took only 15 months to hurdle Congress.

The Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) Act of 2022 mandates companies with more than P100 million assets to develop a scheme to recover the same amount of plastics they produce or face a fine of at least P5 million.

It was the counter-proposal of the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCGs) industry to the single-use plastics ban — the solution backed by environmental groups — that would have forced them to look for alternatives to products such as bottles, wrappers, straws and bags.

On Feb. 11, 2020, a month before the government imposed strict lockdowns due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Sen. Cynthia Villar submitted the first version of what would become the EPR law — Senate Bill No. 1331.

SB 1331 obliged enterprises to redesign their packaging so plastic products may be phased out eventually in their supply chains. It also called for corporations to coordinate with municipal and city waste management offices, so the latter may benefit in terms of direct incentives.

According to a Reuters report, Unilever “directly lobbied Villar last year to focus the government’s plastic regulation on cleaning up sachets rather than banning them.”

The Villars operate several plastic recycling facilities, which the senator was transparent about during the deliberations.

The Villar SIPAG Foundation, which lists the Villars as shareholders, has been operating a plastic recycling facility since 2013. It has three locations that accept and process plastic wastes from barangays — in Las Pinas, Iloilo, and Cagayan de Oro. These plastics are then “processed” and converted into plastic school chairs. The program is undertaken in partnership with the local office of Unilever.

Zoom deliberations

The pandemic got in the way of the EPR bills. The Senate was able to resume deliberations on the proposal by September the following year — over Zoom.

On Sept. 29, 2021, a series of actions were taken to push the EPR bill in the Senate. Villar substituted SB 1331 with a watered-down SB 2425. Instructions for corporations to coordinate with city and municipal waste management offices had been removed. Instead, there was a list of “possible” EPR programs that obliged enterprises may adopt. This language was eventually maintained in the final version of the law.

“I am just being nice to the business sector kasi ang tingin ko, masyadong mabigat iyong single-use plastic ban at this time,” Villar told the plenary during second reading deliberations in January 2022.

It was her daughter, Las Piñas Rep. Camille Villar, who introduced the EPR bill in the House of Representatives.

The bills faced little opposition in the country’s two legislative chambers.

In the Senate, the measure was unanimously approved (is this accurate to say, Ely?). During the second hearing, the senators only clarified if the industry was supportive of the measure. After all, the policy would require the infrastructure to recycle plastic trash. It was during this time when Senator Villar put forth her experience in the recycling industry to convince her colleagues to vote for its passage.

“You know, iyong aking recycling factory ay mura lamang; hindi naman mahal. Ako lamang ang nag-build noon personally. Hindi nga iyong company namin—ako lang, iyong aming foundation. Bakit naman hindi kaya ng Robinson’s at saka ng San Miguel [to build their own recycling facility]?, she said then.

The two companies Villar mentioned — Robinsons Retail Holdings and conglomerate San Miguel Corp. — either have subsidiaries or sister companies that are in the FMCG industry.

Meanwhile, in the House, only six lawmakers voted against the measure, with Kabataan Partylist Rep. Sarah Elago calling it “palliative”.

“This [policy] may be the cause of delay of more effective policies like the single-use plastic ban and even provide more rationale for greater plastic production. It also encourages unsustainable and false solutions to the waste crisis such as chemical recycling, cement kilns, and waste- to-energy incinerators,” she said.

By then, however, it was too late. Less than a week after the hearing, the lower chamber had transmitted its version to the Senate. By May, the bicameral conference committee had ratified a version, which Congress submitted to Malacañang for then President Rodrigo Duterte’s signature. Days before Duterte stepped down from office on June 30, Nestle Philippines released a statement urging him to sign the measure. He took no action. It lapsed into law during the first few weeks in office of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. in July.

In a statement later, Senator Villar contended that the law was “a good start” toward circular economy even as she acknowledged that the law’s limited application to plastic packaging and large enterprises “could be viewed as compromises”.

“Waste recovery in an archipelago is no small matter and will not be cheap. It is time to place the responsibility of retrieving these wastes in the hands of the producers while still calling on the citizenry to do the appropriate thing,” she said. END